Amidst commentaries on American crony capitalism, security feminism, and the democracy movement in Mexico, “Art and the Arab Awakening,” Nama Khalil’s article in Foreign Policy in Focus (2 August 2012), stands out with its colorful, playful, joyful descriptions of the art production that has come to international attention during the “Arab Awakening.” Many celebrations of Arab art have been pouring forth since 2001[i], but the placement of Khalil’s article in a forum for American-Anglophone foreign policy raises important questions about international relations conducted in cultural production[ii]: 1) Why “art?” 2) Why an “awakening?” 3) Why foreign policy? Why do these terms orient the discussion? I want to argue that this approach to art is the flip-side of a policy of humanitarian intervention that minimizes and limits how victimized people may come to participate in global politics.

Early in her catalogue of new works Khalil avers, “Art has also been an ongoing experience for the revolutionary youth that is strengthening civil society and democratic process” (my emphasis). The same bywords reverberated at a conference recently held in Ramallah by a European funding umbrella to glean suggestions from “cultural producers” for ways they could contribute to civil society. Eerily, Khalil’s article reads like a grant application to this EU organization, and posted on a policy advocacy website, it constitutes a call for a new type of humanitarian intervention. Enfolded in the technicolor robes of art is an argument about what a human is and how humans who were “asleep” can experience and exist in a global world of unequal power.

January 2011 is not the first time Arabs have “awakened.” In fact, various commentators have sighted signs of an Arab awakening repeatedly since George Antonius (1938) propounded against Ottoman control. How many times can Arabs wake up before they get on with their day? Or perhaps the more logical question to stem from the repeated sightings is, “How quickly can Arabs fall asleep after such exciting historical moments?” What is this narcoleptic population??

Khalil’s take on awakenings is not just an admonishment to the wooly-eyed. Like any good myth, it is also a proposal for recovering narcoleptics and their (international) families. Wake up, make art, and by making a career you can get a toe in the public sphere and may ultimately reclaim sovereignty. The example that opens Khalil’s article is Faten Rouissi’s project titled, “Street Art – Art in the Neighborhood,” which involved re-painting charred cars set ablaze by Tunisians “expressing their anger and pain,” thus transforming them from “destruction…image[s] of ashes and despair” into “a positive, rejuvenating project” consisting of “blooming objects in bright colors, adorned with revolutionary graffiti” (my emphasis). The self-consciously phoenician phrasing transforms graffiti from a deliberately vandalizing practice designed to assert control over capital and privatized space, into a mere ornamentation pasted onto cliché slogans. But it promises that “after decades of censorship and fear,” civil society and democracy will at last ensue.

At the risk of being an aesthetic heathen, I would counter Khalil’s assumptions about art with a few questions: Why is burning cars automatically “destruction,” and why is scribbling key words automatically “positive” and “rejuvenating”? Arabs have been writing “freedom” and “revolution” for decades, so what exactly is added by looking at this activity via the lens of art? How does sighting “art” become proof of awakening and hence, a basis for a particular type of policy proposal? And thinking about the 1980s school of Intifada-art in Palestine, and the style of “Renaissance (Nahda)” art in early national Lebanon and Egypt, one could also ask, “How does art have to look to be recognized by these policy-makers?”

First consider the standard humanitarian intervention before art is inserted: One may argue that such projects work by recognizing their recipients’ humanity in the minimum that it takes to keep them “alive” (with that quality itself subject to definition by the intervening society).[iii] Claiming the right to protect this minimum, they tell the world’s governments, “Yes, you can outlaw concrete, stationary hair conditioners and playgrounds because they are unnecessary, but you may not deny your victims the minimum nutritional and health requirements per person, for this is the threshold beyond which life cannot be sustained.” For all their generosity, such interventions effectively prohibit beneficiaries from expanding their existence as humans at the donors’ expense. Playgrounds, it turns out, are not only “unnecessary” but also potentially dangerous because they are susceptible to “dual use,” meaning they could be converted for uses that imperil the donors’ own lives. And this conversion is especially likely in times of impoverishment, because, as the aphorism goes, “necessity is the mother of creativity.”

Now consider how art works as a term for human activity. Art is that which exists for itself—good art, that is. The other stuff, made without sufficient self-consciousness and institutional orientation, is propaganda or craft.[iv] According to a Kantian philosophy of humanity, we achieve our highest capacity as humans in the realm of uselessness. Here we appreciate rightness not for what it can get us but simply because it is right. In behavior this is morality; in organization, aesthetics. It is in this capacity that humans have dignity, and those who can only see use value lack dignity:

This project celebrates an extraordinary present, a nation’s dream for freedom and dignity. Each car also represents agency, solidarity, and hope in the future of the revolutionary movement.

To call something art is to empty it of everyday, political, historical meaning. It is to take cars (objects with use value and symbolic value in class societies) and transform them into bright colorful objects (after their use value was wrested from them in a rampage against rank and class control). “Rainbow-painted” objects that are no longer cars in crisis but sites of “creative collectivity” and politely sprayed “self-expression” that is no longer aggressive graffiti both fit this Kantian scheme as signs and cultivators of penultimate humanity: dignified, moral, and guided by its own agency, neither trapped in a crass relationship to the everyday nor trapped by others’ crassness in everyday exploitation. By corollary, the person who promotes dignified and dignifying aesthetic and moral activity is paradigmatic of humanity’s maximum potential.

With art production, humanity is recognizable in its luxury—not its caloric minimum but its maximum celebration of the feast of freedom. The former victims don’t just kick out dictators; they progress to showing appreciation for that which has value only in itself and for itself. This is not to say social hopes are not invested in true art. Rather, it is to attend to the glorified distinction between artistic propaganda and adorned objects marking an “extraordinary present.” The new forays into the aesthetic mark the narcoleptic population’s arrival at the threshold of maximum humanity. And they have done so without violence or any other factor that could threaten a former donor’s own (maximum) humanity. They reveal to donors that they do not deserve those dictators; yet, at the same time, their art experiences must be supported or they could lose awareness and lapse back into deep slumber, or worse violence:

Fadi Alharby, a Yemeni painter says that "many people think the revolution in Yemen is based on violence, […] but for me it is based on art, because art is a human right, it is freedom." The uprising has in fact been marred by violence […] in sharp contrast to the peaceful scenes at Change Square, where art continues to bring people together. The Youth for Freedom and Justice Movement created a studio-tent space at Change Square for artists. […] "Art plays an important role in awareness. The number of people that come to our studio is a positive indicator of the civic state we hope for in the future."

The support for art that Khalil calls for should be seen as another type of humanitarian intervention, with all the attendant definitions of who can participate in humanity, for whose ultimate benefit, and how. To wit, “dual use” objects feature in this relationship when former victims take practical things and turn them into invaluable works of art: cars become “blooming objects in bright colors,” walls become “blank canvasses,” a central urban square can become a studio-tent. This is the non-violent version of the dual use dilemma: an opulent display of the ability to transform material whose starting point is the aphorism that “creativity is the mother of necessity.” Creative people will provoke awareness in others of things they did not know to be necessary in their lives but must learn if they are going to be proper citizens. Once people demonstrate their proclivity to non-violent “dual use,” they truly deserve self-governance, or rather, civil society:

Art creates a dialogue between the artist and the audience. Under the old authoritarian systems, this dialogue was so often uni-dimensional. As a result of the tumult in the Arab world, the dialogue has expanded considerably. In fact, it has helped to foster a more vibrant civil society and to point the way toward more durable democratic institutions.

If Khalil’s article reads like an EU grant application, this stylistic aspect underscores the new constraints an “awakening” notion of art ushers in: first, there are the burdens of depending on outside support for art production. EU funding, for example, entails endless paperwork, mind-boggling terminology, and interminable hours spent on reporting procedures. Nor is this new claim on energies and imaginations purely logistical. As one Palestinian artist recently put it, physical force has been replaced by emotional blackmail and a hegemonic definition of what constitutes “art.” So while we applaud the boldness with which artist now criticize fleeing rulers, should we not also listen closely for whisperings against fly-by-night curators and funders who work though gate-keepers who are often as partisan and rigid as the old state regimes?

Second, there are aspects of Arab art that Khalil does not address because they must be excluded for the targeted type of humanity to appear as properly wakeful, dutiful, and deserving. Among them are external critique, anti-colonialism and neo-liberalism, internal economic critique, explicit ideologies, and anything lacking an air of spontaneity, cuteness, and clever humor. One might disparage certain aesthetic choices, but if some styles and media ignore today’s fashions, does that mean those that conform are automatically livelier? Is cosmopolitan a synonym for cognizant?

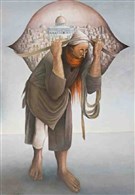

Lastly, the histories of regional cultural production are almost non-apparent through this lens, and by back-grounding them, Khalil counter-intuitively invests in the idea that Arabs never before made art that was both activist and internationalist. Where are the Palestinian painters of the Nakba and Intifada, such as Suleiman Mansour and Ismael Shammout, or the Lebanese artists of Arab nationalism and communism, such as Saloua Raouda Choucair, Aref Rayyes, and Seta Manoukian? The polymaths, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Abdel-Rahman Munif, and Fateh Mudarris? Is it that they were asleep or that their beliefs constitute the policy-maker`s nightmare?

The danger is that in such stories of awakening, “art” becomes a code word for having a proper consciousness. The term’s connotations—gutsy, personal, authentic—hide the conformity that is imposed in this maximalist humanitarian intervention. As long as the Arab Rip van Winkle pursues dual-use creativity that is aesthetic, moral, and dignified he can be accepted in the human family. But the warning is clear: should he lapse into violence and ideology (if Islamists win the elections and stop promoting art as a “tool for building a cultured community”), he loses the right to sovereignty. Just look at Iraq, where the most flourishing art culture in the region, characterized by free art schools and a plethora of professional opportunities, was massacred. Uproar ensued when ancient artifacts of “humanity’s heritage” were looted, but silence enshrouded contemporary Iraqi art, as if it had never existed. In fact, many of the lesser-known Iraqi artists who remained inside the country after 1991 turned to reproducing nineteenth-century Orientalist paintings. They had discovered a new souvenir market for the diplomatic and humanitarian delegates who desired to bring home images of a nargileh-drugged, bed-ridden populace whose siege the same delegates effectively supported by keeping it on a “minimal life-support” system.

With art as a policy of “like us,” we are prone to support an elitist Kantian definition of humanity, one stemming from the thinking of men living two hundred years ago in financial and social security. It is a definition that has little to do with the conditions of living that have provided the ground for these “awakenings.” Who has woken up? Who risks being lulled into passivity and dreamland?

[i] See the folllowing important critiques of this phenomenon: Jessica Winegar, "The Humanity Game: Art, Islam, and the War on Terror." In Anthropological Quarterly, 81, no.3 (Summer 2008), 651-681; Maymanah Farhat, "Imagining the Arab World: The Fashioning of the `War on Terror` through Art." In Callaloo, 32, no.4 (Fall 2009), 1223-1231.

[ii] In fact, Khalil`s article is but one example of a trend. See also Ali Khaled, "From the Arab Spring Comes a Cultural Awakening." In The National, 18 May 2011. In addition to numerous curatorial and art residency calls, Harvard University hosted a conference this spring titled, "The Arab Awakening: A Flourishing of Art and Culture." My critique should be read as a response to this perspective generally, especially for how it comes to lend itself to policy formulation.

[iii] The following discussion of humanitarianism`s "minimum humanity" is inspired by an unpublished work in progress that Peter Lagerquist has kindly shared.

[iv] Generally the category "Art" excludes exactly the material she discusses -- graffiti, popular music, cartoons, banners, landscaping, and...well...car painting. This raises questions of what is being gained by contravening classical usage of the category.

![[Suleiman Mansour, \"Camel of Hardships\" (1973) detail. Image courtesy of the artist]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/CamelofHardships_SuleimanMansour.jpg)